Foreword

Logic

We can prove correctness of our algorithms (and programs) if we:

- understand what correctness means (i.e. the exact specification)

- can give a completely convincing argument that our code conforms to the correctness specification.

Definition, according to The Chambers Dictionary (TCD):

- logic /loj’ik/ (noun)

- The science and art of reasoning correctly

- The science of the necessary laws of thought

Completely Convincing Arguments: Logical Fallacy

If each man had a definite set of rules of conduct by which he regulated his life he would be no better than a machine. But there are no such rules, so men cannot be machines.

— A. M. Turing, Computing Machinery and Intelligence, 1950.

More formally stated as a rule of inference:

This is an example of a logical fallacy – an incorrect form of argument where the premises (stated above the bar) do not entail the conclusion (stated below the bar).

Completely Convincing Arguments: Sound Inferences

- A rule of inference is sound if the conclusion is a logical consequence of the premises.

- In a sound rule of inference it is impossible for all the premises to be true and the conclusion to be false. For example:

- Sound arguments can be constructed this way to prove theorems from axioms (self-evident statements that require no proof).

- A formal proof can be stored in a file and checked by a computer.

What is Hoare Logic?

- Introduced by Sir Tony Hoare in 1969.

- Followed in the footsteps of R. W. Floyd (who devised a similar system for flowcharts in 1967).

- Allows us to formally prove that a program satisfies its specification (contract).

Hoare logic provides a way of formally defining the semantics of a programming language (so-called axiomatic semantics).

- Hoare logic is a logic for reasoning about programs. It involves:

- a few basic axioms

- some sound rules of inference

- To state and prove properties of programs using Hoare logic we need to understand the following terms:

- preconditions

- postconditions

- Hoare triples

- invariants

- variants

Preconditions

- A precondition is a property that has to be true just before a program is executed (i.e. just before an operation is performed).

- As a contract specification, a precondition can be treated as an assumption by the programmer.

- An (informal) example:

- “The initial values of x are in the range [−10, 60].”

- Intuitively, if a program receives inputs (i.e. starts executing in a state) which violates the precondition, then it has no obligation to do anything sensible.

Postcondition

- A postcondition is a property that has to be true once the program is executed and terminates.

- As a contract specification, a postcondition can be treated as an requirement (i.e. a contractual obligation to be fulfulled).

- An (informal) example:

- “The array will be stored in non-decreasing order when the program finishes.”

- Intuitively, a program promises to achieve the postcondition (provided that the precondition is met). [It is also usually desirable for programs to terminate.]

Hoare Triples

- A Hoare triple has the form:

{𝑃𝑅𝐸} 𝑃𝑟𝑜𝑔 {𝑃𝑂𝑆𝑇 } - where

𝑃𝑅𝐸is the precondition𝑃𝑂𝑆𝑇is the postcondition𝑃𝑟𝑜𝑔is the program.

- A Hoare triple states that

𝑃𝑟𝑜𝑔will establish𝑃𝑂𝑆𝑇on completion, provided𝑃𝑅𝐸holds before execution of𝑃𝑟𝑜𝑔.

Some Examples of Hoare Triples

{true} x:=10 {𝑥 > 0}

{true} x:=10 {𝑥 = 10}

{𝑥 > 2} x:=x+1 {𝑥 ≤ 3}

{true} x:=x+1 {???}

- How can we express that the value of

𝑥has increased by executing the program statementx:=x+1?{true ∧ 𝑥 = 𝑣} x:=x+1 {𝑥 = 𝑣 + 1}- where

𝑣is a fresh variable.

Hoare Logic

Hoare Logic: Axioms

- Two axioms of Hoare Logic:

{P} skip {P}: This is a Hoare triple indicating that performing theskipoperation (which does nothing) does not change the truth of the assertionP. Here,Pis the precondition,skipis the program statement, andPis also the postcondition. It implies that ifPis true before performingskip, it remains true afterwards.{P₀} x := E {P}: This is another Hoare triple, describing an assignment operation.x := Emeans the variablexis assigned the value of the expressionE. In this axiom,P₀is a special precondition that represents the state of P but with every free occurrence ofx(that is, occurrences ofxnot bound by other variables or function scopes) replaced by the expressionE. IfP₀is true before the assignment, thenPwill be true after the assignment.

Hoare Logic: Assignment Examples

In practice, to check a Hoare triple {𝑃𝑅𝐸} x:=E {𝑃𝑂𝑆𝑇} we check 𝑃𝑅𝐸 → 𝑃𝑂𝑆𝑇₀. Examples:

{𝑥 + 1 = 3} x:=x+1 {𝑥 = 3}

{𝑥 + 1 = 3 ∧ 𝑦 = 0} x:=x+1 {𝑥 = 3}

{𝑦 + 𝑧 = 5} x:=y+z {𝑥 ≥ 5}

Hoare Logic: Rules of Inference

consequence

The line in the picture is the notation for a proof rule used in Hoare Logic, which stands for “deduce” or “derive” in logical deduction. In Hoare Logic, this symbol is usually used to indicate that if the above condition (premise) holds, then the following conclusion will also hold.

composition

- Suppose we want to prove:

{𝑦 = 𝑧} x:=z+1; z:=y+1 {𝑧 = 𝑥} - Let

𝑅1 = 𝑦 + 1 = 𝑥, so we need to prove (left sub-goal):{𝑦 = 𝑧} x:=z+1 {𝑦 + 1 = 𝑥}(check𝑦 = 𝑧→𝑦 + 1 = 𝑧 + 1) - And the right sub-goal:

{𝑦 + 1 = 𝑥} z:=y+1 {𝑧 = 𝑥}(check𝑦 + 1 = 𝑥→𝑦 + 1 = 𝑥)

conditionals

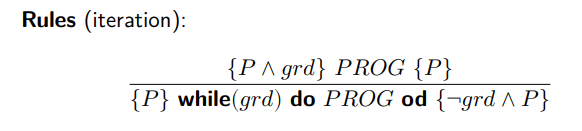

iteration

The rules are in two parts:

- Loop Invariant:

Pis a loop invariant.Pholds as the program enters the loop and is preserved after each iteration of the loop. The loop invariant is a key concept for verifying the correctness of loops. - Iteration Rule:

{P ∧ grd} PROG {P}: This means that if the conditionP(the loop invariant) andgrd(the guard or condition of the loop) are both true before each iteration of the loop, thenPwill still be true after the execution ofPROG(the body of the loop).{P} while (grd) do PROG od {¬grd ∧ P}: For the loop as a whole, ifPis true at the start of the loop, then after executingPROGin each iteration of the loop untilgrdis no longer true (i.e., the loop ends), the final state will be¬grd ∧ P, meaning the loop invariantPis still maintained and the guardgrdis false.

Examples

Programs with Loops

Suppose we have the following looping program with integer program variables 𝑟, 𝑛 and 𝑁 (which is treated as input):

n:=N; r:=1; while(n>1) do r:=r*n; n:=n-1 od

- What does this program compute?

{𝑁 > 0} n:=N; r:=1; while(n>1) do r:=r*n; n:=n-1 od {𝑟 = 𝑁!}

Apparently, this program implements the factorial function. How can we prove this?

Let’s trace the execution:

| Iteration | r | n |

|---|---|---|

| Iteration 0 | 𝑟 = 1 | 𝑛 = N |

| Iteration 1 | 𝑟 = N | 𝑛 = N - 1 |

| Iteration 2 | 𝑟 = N * (N - 1) | 𝑛 = N - 2 |

| Iteration 3 | 𝑟 = N * (N - 1) * (N - 2) | 𝑛 = N - 3 |

- According to the definition of factorial:

N! = N(N - 1)(N - 2)⋯1 - For every iteration of the loop:

N(N - 1)(N - 2)⋯1=r * (n!)- Iteration 0:

𝑟 = 1,𝑛 = N, sor * (n!)=N(N - 1)(N - 2)⋯1 - Iteration 1:

𝑟 = N,𝑛 = N - 1, sor * (n!)=N(N - 1)(N - 2)⋯1 - …

- Iteration 0:

- So,

N! = r * (n!)holds initially and after each loop iteration. - Finally,

N! = r * (n!) ∧ n > 0remains true throughout the loop, even after the loop ends. This proves that the given program segment correctly calculates the factorialN!. - After the loop terminates:

- The loop invariant will be true

N! = r * (n!) ∧ n > 0. - The loop guard will be false, i.e.

¬(𝑛 > 1)will hold.

- The loop invariant will be true

Proving correctness using loop invariants is similar to proofs by induction:

- A base step: the loop invariant is true initially,

- Inductive step:

𝑃𝑅𝑂𝐺(i.e. loop body) preserves the invariant when the guard (𝑔𝑟𝑑) holds, - Sufficiency: when the loop terminates, the invariant and

¬𝑔𝑟𝑑together imply the post-condition.

Finding loop invariants can be rather difficult in practice.